The Link Between Authentic Leadership, Organizational Dehumanization and Stress at Work

[La relación entre el liderazgo auténtico, la deshumanización organizacional y el estrés en el trabajo]

Mario Sainz1, Naira Delgado2, and Juan A. Moriano3

1University of Monterrey, Mexico; 2Universidad de La Laguna, Spain; 3Universidad Nacional de EducaciĂłn a Distancia, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a9

Received 3 October 2020, Accepted 5 May 2021

Abstract

Organizational dehumanization has detrimental consequences for workers’ well-being. Previous research has focused on organizational factors that trigger workers’ dehumanization or stress at work. However, less is known about the factors that can protect workers against the detrimental effects of dehumanization. In the present research, we performed a correlational study (N = 930) and a direct replication of it (N = 913) to analyze 1) the mediation role of organizational dehumanization in the relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work, and 2) the possible moderation of organizational identification and the frequency of leader-follower interactions. The results indicated that higher authentic leadership predicted lower organizational dehumanization and stress at work. Moreover, organizational dehumanization mediates the relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work.

Resumen

La deshumanización organizacional tiene efectos muy perjudiciales para el bienestar profesional. Estudios previos se han centrado en identificar factores organizacionales que desencadenan la deshumanización de los trabajadores o el estrés en el contexto laboral. Sin embargo, se conoce muy poco sobre los factores que pueden proteger a los trabajadores de los efectos negativos de la deshumanización. En esta investigación llevamos a cabo un estudio correlacional (N = 930) y una replicación directa (N = 913) para analizar 1) el papel mediador de la deshumanización organizacional en la relación entre liderazgo organizacional y estrés en el trabajo y 2) la posible moderación de la identificación con la organización y la frecuencia de la interacción líder-seguidores. Los resultados mostraron que un mayor nivel de liderazgo auténtico predecía un menor nivel de deshumanización organizacional y de estrés en el trabajo. Además, la deshumanización organizacional media en la relación entre liderazgo auténtico y estrés en el trabajo.

Palabras clave

Liderazgo auténtico, Deshumanización organizacional, Desequilibrio en el trabajo, Identificación con la organizaciónKeywords

Authentic leadership, Organizational dehumanization, Work imbalance, Organizational identificationCite this article as: Sainz, M., Delgado, N., and Moriano, J. A. (2021). The Link Between Authentic Leadership, Organizational Dehumanization and Stress at Work. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 85 - 92. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a9

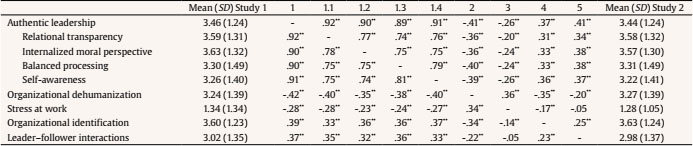

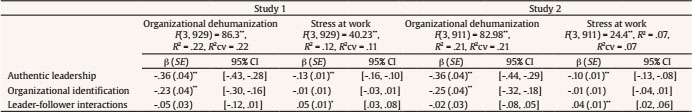

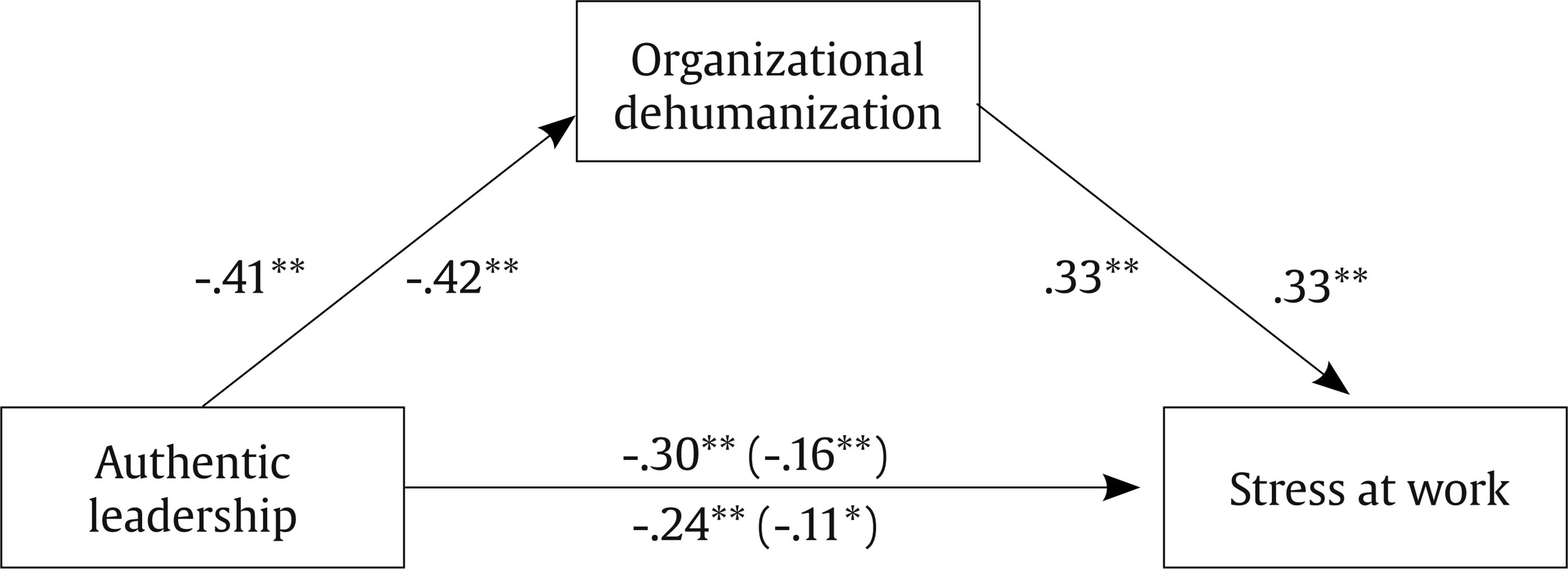

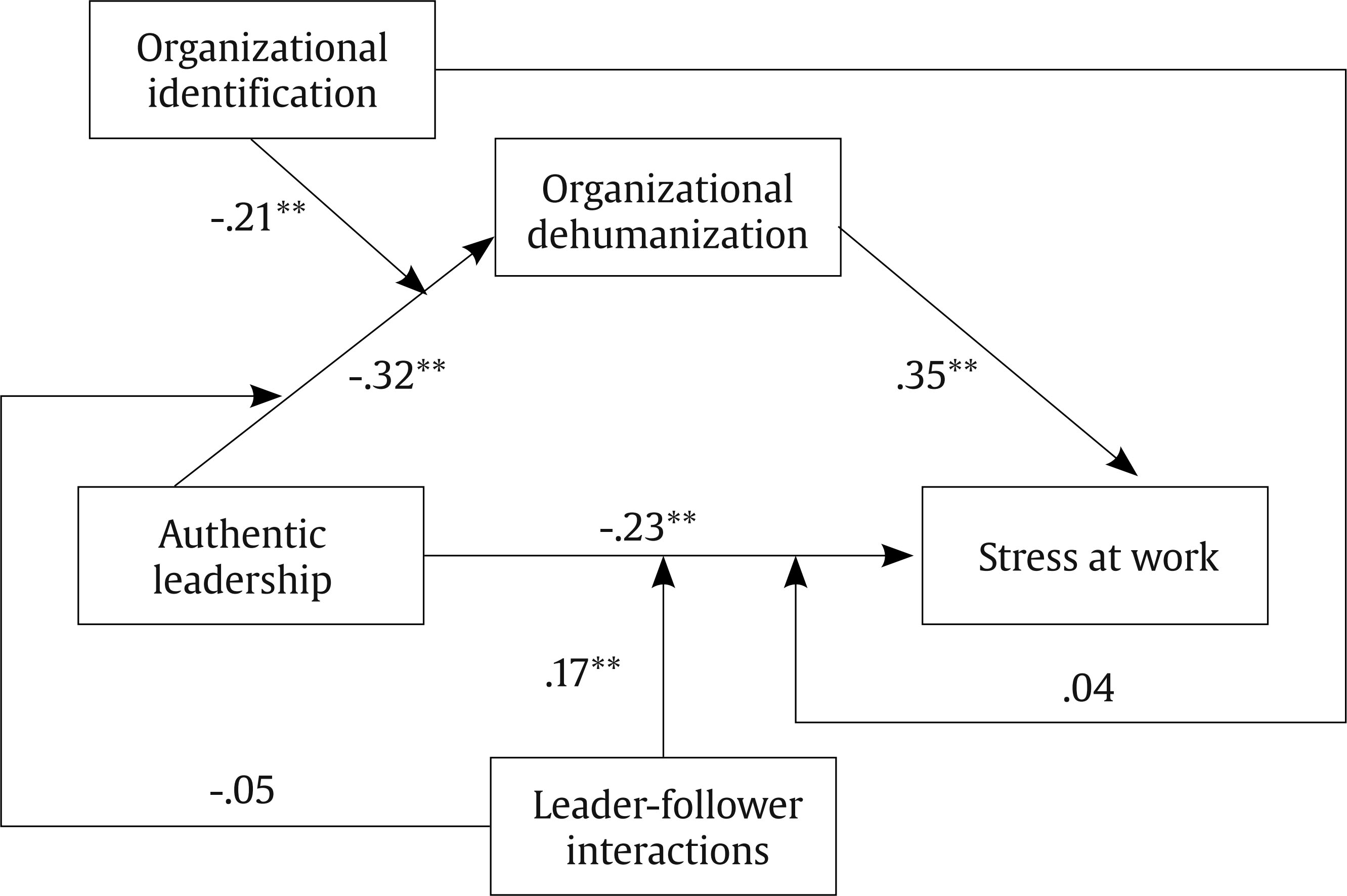

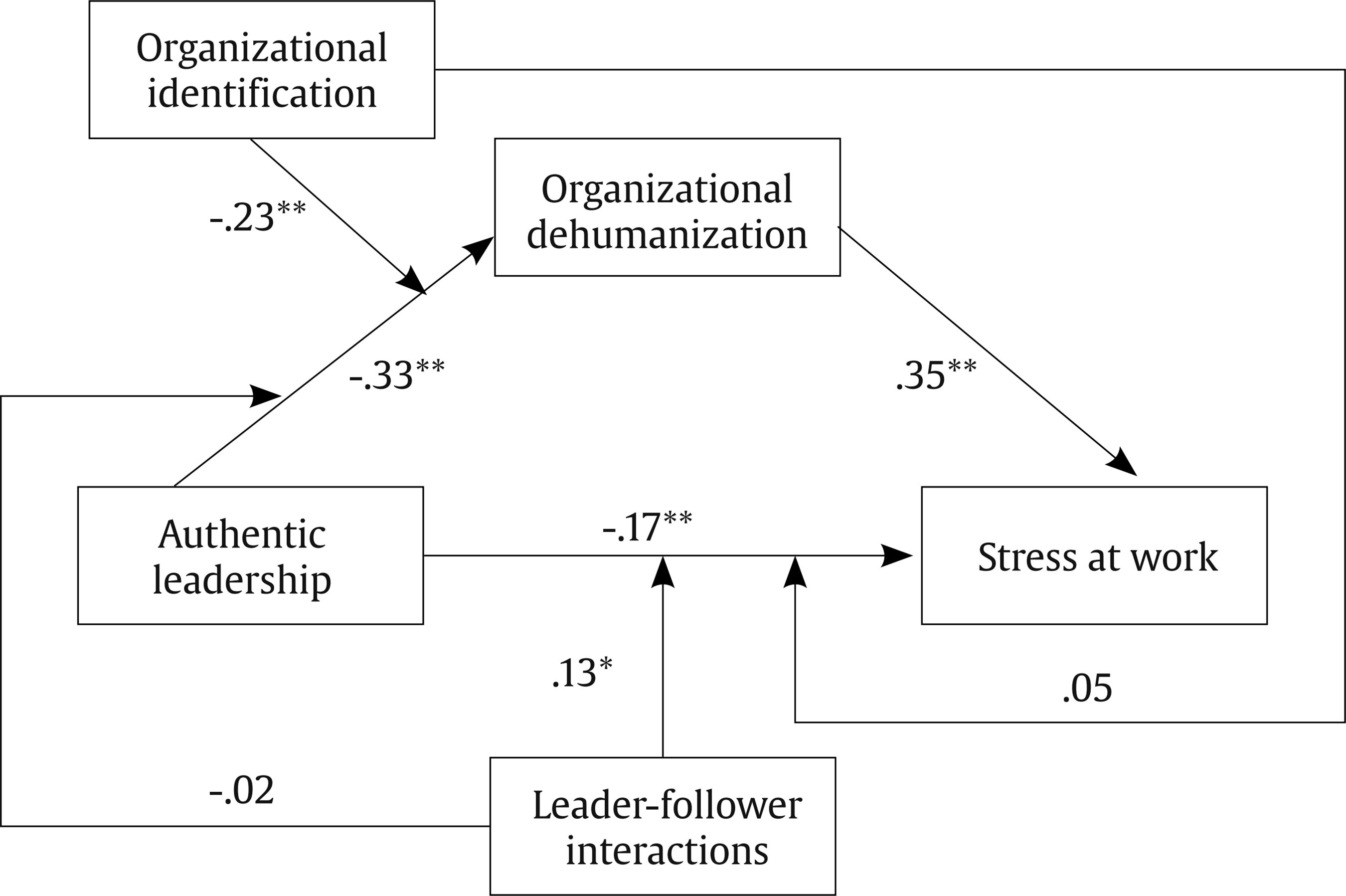

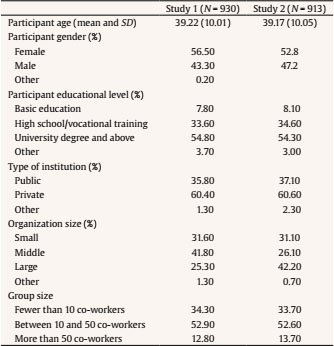

ndelgado@ull.es Correspondence: ndelgado@ull.es (N. Delgado).Workers’ perceptions of being treated and perceived as objects or resources within their companies (i.e., organizational dehumanization) have detrimental consequences for their well-being (Caesens et al., 2017). Previous research has identified several factors that could trigger workers’ (self- or other-)dehumanization. Scholars have explored the effect of the status of a worker’s position (Terskova & Agadullina, 2019; Valtorta et al., 2019a); the types of tasks that workers carry out, such as routinized work, fragmentation of activities, or dependence on machines (Andrighetto et al., 2017; Bell & Khoury, 2011); supervisors’ emotional distance displayed toward subordinates (e.g., Väyrynen & Laari-Salmela, 2018); and the leadership styles that workers identify in their direct supervisors (Caesens et al., 2018). Most of this previous research has focused on factors that worsen workers’ daily routines and increase negative psychological outcomes. Less is known, however, about factors that can protect workers against the perception that they are treated as resources (i.e., organizational dehumanization) and thus promote employees’ well-being within their companies. Therefore, our aim in the present research was to analyze a specific factor that could improve workers’ well-being as they perform their daily routines. Specifically, we focused on the possible protective influence that a specific type of leadership can exert on workers: an authentic leadership style (Walumbwa et al., 2008). This leadership style has previously been identified as having positive outcomes in working environments (e.g., Laschinger & Fida, 2014). Thus, we expected that authentic leadership would reduce workers’ perception of being dehumanized by the company, therefore creating conditions in which workers will be less likely to suffer from stress when performing their work routines. Organizational Dehumanization Dehumanization is one of the most serious and degrading forms of social perception. It is a psychological phenomenon whereby people perceive that other human beings are not fully human or are less human than ingroup members (Haslam, 2006; Haslam & Loughnan, 2014; Leyens et al., 2000). Dehumanization is a pervasive phenomenon with blatant and subtle expressions, which could affect a large number of groups (not just extremely negative outgroups) and has important consequences in social interaction (Andrighetto et al., 2014; Goff et al., 2008; Leidner et al., 2013). Despite the considerable number of studies conducted in this field in the past two decades, only recently have social psychologists begun to investigate this phenomenon in the workplace (Christoff, 2014). In working environments, previous evidence has mentioned the construct of organizational dehumanization, which refers to an employee’s perception of being mechanistically dehumanized or objectified by the organization (e.g., Andrighetto et al., 2017; Caesens et al., 2017). Workers in modern organizational settings often report the extremely negative perception of being treated as machines, numbers, or parts that can be replaced (e.g., Bell & Khoury, 2011; Christoff, 2014). This dehumanized perception (i.e., organizational dehumanization) has been found to be associated with several factors. Some are related to quality of work, such as the types of tasks that workers carry out (Baldissarri et al., 2014, 2019), the specific type of work they have to perform (e.g., dirty jobs; Valtorta et al., 2019a, 2019b), or even the physical space in which workers perform their activities (Taskin et al., 2019). Other factors are related to the hierarchical relationship within the company, such as power dynamics (Gwinn et al., 2013; Lammers & Stapel, 2011) or perceived leadership styles (Caesens et al., 2018). In this regard, on the one hand, research has shown that the experience of power triggers mental processes that lead to dehumanization: people in situations of power have a reduced tendency to adopt others’ points of view (Galinsky et al., 2006), maintain a greater interpersonal distance (Lammers et al., 2011), and increase the mechanisms of deindividualization (Dépret & Fiske, 1999; Gruenfeld et al., 2008), which is closely linked to dehumanization (Haslam & Bain, 2007). On the other hand, the role of supervision and of perceived leadership styles could also be a key determinant in triggering dehumanization at work. For instance, previous evidence has highlighted that perceiving that a supervisor engages in abusive behaviors, such as ridiculing employees, yelling at them, or denigrating them (i.e., abusive supervisor; Tepper, 2000), leads employees to feel dehumanized by their organization, which has important consequences for turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and affective commitment (Caesens et al., 2018). These findings highlight the detrimental impact that abusive leaders can have on workers’ satisfaction within their companies and also on their personal well-being. Nevertheless, when addressing the role of leadership styles in perceived organizational dehumanization, the effects of other types of leadership, apart from abusive style, on perceived organizational dehumanization, as well as the consequences of this perception, have not been explored. The aim of this research is to address the positive role that a particular leadership style could play in ameliorating organizational dehumanization, as well as its consequences. Specifically, we focused on the role that an authentic leadership style (Walumbwa et al., 2008) might have on workers’ perception that they are dehumanized. Influence of Supervisors on Workers: Authentic Leadership Style Perceived leadership style that workers identify in their direct supervisor has a great influence not only on processes related to the working environment (e.g., workers’ performance, job satisfaction, turnover intentions) but also on an individual level (e.g., health conditions, psychological distress, subjective well-being; Haslam et al., 2011). Hence, the range of detrimental consequences that could potentially arise when workers are under the supervision of destructive (Einarsen et al., 2007) or abusive (Tepper, 2000) leaders could be wide. However, certain leadership styles can have a positive influence on workers by shaping the quality of their immediate work environments, which can improve their job satisfaction and well-being (Ding & Yu, 2020; Kuoppala et al., 2008). This, in turn, encourages workers to voluntarily contribute to organizational goals achievement (Reicher et al., 2005). One of the leadership styles that has a potentially positive impact, both on workers and on organizations, is authentic leadership style. According to the authentic leadership model (Moriano et al., 2009; Walumbwa et al., 2008), authentic leaders are able to create positive work environments and ethical climates by acting in ways that are consistent with their self-concepts, show moral character, and are concerned with follower development (and not their own interests; Jex & Britt, 2014). Based on the positive organizational psychology literature, authentic leaders are supposed to foster self-awareness (e.g., knowledge about their strengths and limitations as leaders, and their ability to influence others), an internalized moral perspective displayed on a daily basis (e.g., ability to behave according to their values), the balanced processing of information (e.g., taking into account others’ opinions), and transparency in the relationship between leaders and their employees (Walumbwa et al., 2008). Simply put, authentic leaders are those who try to maintain internal coherence between their moral values and their behaviors, or who have transparent and sincere relationships with their employees that promote employees’ well-being (Gardner et al., 2005; Gardner et al., 2011). Previous research has highlighted the positive consequences that being in contact with authentic leaders may have on employees. For instance, it improves the overall performance capability of the organization (Banks et al., 2016; Lyubovnikova et al., 2017); increases job satisfaction (Azanza et al., 2013); boosts organizational commitment or work happiness (Jensen & Luthans, 2006); decreases turnover intentions (Azanza et al., 2015); and even promotes intrapreneurial behaviors among workers (Edú-Valsania et al., 2016). In general terms, the presence of an authentic leadership style within a company seems to act as a protective factor by not only promoting employees’ well-being but also providing positive outcomes for the company (i.e., lower worker turnover). A well-developed stream of research links perceived social support from a leader to lower levels of perceived work stress (e.g., Van Dierendonck et al., 2004). Positive forms of leadership, such as an authentic leadership style, can help employees to feel engaged and supported in their jobs (Azanza et al., 2015; Martínez et al., 2020). In addition, they are associated with lower levels of stress in the workplace (Skakon et al., 2010). Furthermore, authentic leaders’ transparency and internalized moral perspective increase trust among subordinates. Progressively, trust generates security in interactions, which, in turn, decreases stress (Molero et al., 2019; Rahimnia & Sharifirad, 2015). By recognizing and rewarding employees for their work, leaders can encourage them to believe in themselves and thus resolve the effort-reward imbalance at work (Weiß & Süß, 2016). Therefore, in the present project, we proposed that an authentic leadership style will protect workers against the negative effects of organizational environment on their well-being by promoting the perception that they are regarded and treated as human beings and not as mere resources or machines within their companies. Specifically, we focused on a psychological outcome that has not been previously addressed in the study of organizational dehumanization: stress at work (Siegrist et al., 2004). In light of the above, we considered possible stress at work to be another negative outcome for workers. However, the presence of stress at work might be reduced when authentic leadership is identified, and perceived organizational dehumanization might decrease. Overview Our main goal is to analyze the extent to which an authentic leadership style acts as a protective factor against organizational dehumanization and stress at work. We also wish to examine if the possible relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work could be mediated by organizational dehumanization. Previous studies have shown that organizational dehumanization is influenced by employee-organization relationship. Specifically, Caesens et al. (2017) showed that high levels of perceived organizational support (POS) diminished organizational dehumanization perceptions among employees, and Caesens et al. (2018) explored the role of abusive supervision style in organizational dehumanization. The current study continues and expands previous research in the field, focusing on employee-leader relationship. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that an authentic leadership style will negatively correlate with workers’ perceptions of organizational dehumanization and stress at work (Hypotheses 1 & 2). Moreover, we also expect that the relationship between an authentic leadership style and stress at work will be mediated by perceived organizational dehumanization (Hypothesis 3). Finally, as previous research has shown, higher identification with the company and greater contact with company’s leader are two of the most common variables that could shape the strength of the relationship we tested (e.g., Edú-Valsania et al., 2016). Thus, the possible moderation of the role of organization identification (moderator 1) and the perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions (moderator 2) were explored in the aforementioned relations (i.e., the effect that an authentic leadership style has on both organizational dehumanization [Hypotheses 4a & 4b]/stress at work [Hypotheses 5a & 5b]). We collected a large sample of workers to address our goal. Then, we split the sample in two groups to perform a first study that allowed us to explore the relationship between the variables, and a direct replication of this study to confirm the pattern of results. Participants were randomly assigned to the studies. Data and materials implemented in these studies can be found online (osf.io/b5vd3/). In this study, we aimed to analyze the extent to which perceived authentic leadership style protects workers from feeling that they are mere resources in their companies and how this helps them to maintain an adequate effort-reward balance when performing their daily tasks (i.e., stress at work). Preregistration of hypotheses can be found online (osf.io/b8s24). Participants. Sample size was calculated by using G-power analysis for a small effect size in a regression model (Faul et al., 2009). A minimum of 652 participants was required (one predictor, f2 = .02, α = .05, 95% power). The final sample was composed of 930 Spanish workers (see Table 1 for a detailed description of the sample) from the general population. Measures. Once the participants had agreed to participate, they were presented with the following information: Authentic leadership style. An adapted Spanish version of the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (Walumbwa et al., 2008) was used (Moriano et al., 2011). The adapted scale was composed of 16 items (α = .95) organized in four subscales: relational transparency (five items, e.g., “My leader openly shares information with others”, α = .86), internalized moral perspective (four items, e.g., “My leader is guided in his/her actions by internal moral standards”, α = .83), balanced processing (three items, e.g., “My leader encourages others to voice opposing points of view”, α = .85), and self-awareness (four items, e.g., “My leader is clearly aware of the impact he/she has on others”, α = .87). Participants reported the extent to which their direct supervisors engaged in these behaviors or attitudes. We computed a general scale based on the average of the items. The answers provided ranged from 0 (never) to 6 (always). Organizational dehumanization. Participants indicated the extent to which they considered that their organizations considered them to be resources, by using 11 items (e.g., “My organization considers me to be a number”, α = .92) from Caesens et al. (2017). We computed a general scale based on the average of the items. The answers provided ranged from 0 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). Stress at work. To measure stress at work, we included 15 items from Siegrist et al. (2004). This scale differentiated between extrinsic effort (five items, e.g., “Over the past few years, my job has become more and more demanding”, α = .78) and reward factors (10 items, e.g., “Considering all of my efforts and achievements, I receive the respect and prestige I deserve at work”, α = .79). To capture the possible imbalance between workers’ efforts and the rewards they receive during their daily routines (i.e., stress at work), a score was calculated by dividing the former factor by the latter (higher scores reflect more stress at work). Organizational identification. Identification with the company was measured using eight items (e.g., “When someone criticizes my organization, I feel personally insulted”, α = .87; Mael & Ashforth, 1992). We computed a general scale based on the average of the items. Answers ranged from 0 (not at all) to 6 (completely). Perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions. The frequency of contact with the direct supervisor was measured using five items (e.g., “How often do you meet with your supervisor?”, α = .74; Azanza et al., 2018). We computed a general scale based on the average of the items. The answers provided ranged from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). Finally, participants provided some demographic information (age, gender) and a variety of measures related to the characteristics of their institutions (type of institution and size of the organization). Procedure. Participants completed a paper-and-pen questionnaire that included the variables of interest in this study, at the end of which a section with sociodemographic variables was included. To recruit participants, we used an exponential non-discriminative snowball sampling. First, we contacted the students of a master in occupational risk prevention at a Spanish University to request their participation in this study, provided they met two conditions: 1) they belonged to a work group of at least four employees, even if they did not perform similar jobs or functions, and 2) the group was coordinated by the same leader. These workers then asked their coworkers to collaborate in this study and gave them a pack containing a document requesting their participation and providing instructions, and stressing anonymity and confidentiality of their responses; the questionnaire itself; and an envelope to return the completed material to the coworker who handed it out to them. The time needed to complete the questionnaire ranged from 15 to 30 minutes. First, we computed descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among measures included in the study (Table 2). Results indicated that authentic leadership was negatively related to organizational dehumanization and to stress at work, but positively related to organizational identification and to the perceived frequency of leader-follower interaction. Second, we calculated regression analyses to identify the predictive capability of an authentic leadership style in organizational dehumanization and in stress at work (Table 3). The results showed that, as expected, authentic leadership negatively predicted organizational dehumanization and stress at work. Thus, the more people perceived that their supervisors engaged in an authentic leadership style, the more they felt that they were treated as humans by their organizations, and the lower the levels of stress they reported when performing their jobs (supporting our Hypotheses 1 and 2). This effect remained significant even when including organizational identification and the perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions in regression analysis. Table 2 Descriptive Analysis and Correlations for the Variables Included in Studies 1 and 2   Note. Results below the diagonal are for Study 1, and results above the diagonal are for Study 2. **p < .01. Table 3 Multiple Regression Analyses of Authentic Leadership Factors on 1) Organizational Dehumanization and 2) Stress at Work, including Organizational Identification and Perceived Frequency of Leader-Follower Interactions as Control Variables, for Studies 1 and 2   Note. Coefficients are non-standardized. *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01. Finally, we computed mediation analyses to test the indirect effect of organizational dehumanization in the relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work, by using PROCESS (model 4, bootstrapping 10,000 samples, 95% CI; Hayes, 2018; Figure 1). Results indicated that organizational dehumanization partially mediated the relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work (indirect effect = -.14, SE = .02, 95% CI [-.18, -.11]), supporting Hypothesis 3. Additionally, we computed a moderated moderation analysis by using organizational identification (moderator 1) and the perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions (moderator 2) as moderators in the relationship between an authentic leadership style and organizational dehumanization/stress at work (PROCESS, model 10, bootstrapping 10,000 samples, 95% CI; Figure 2). On the one hand, results regarding moderation of organizational identification indicated that interactions between authentic leadership and organizational identification were not significant (interaction effect = -.04, SE = .03, p = .124; 95% CI [-.10, .01]). Thus, we did not identify the expected moderation effect of organizational identification on organizational dehumanization (Hypothesis 4a). Moreover, results indicated that the interaction between authentic leadership and organizational identification did not moderate the effect on stress at work (interaction effect = .04, SE = .03, p = .183; 95% CI [-.02, .09]), in opposition to our moderation Hypothesis 4b. On the other hand, results regarding moderation of the perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions indicated that the interaction between this variable and authentic leadership in organizational dehumanization was not significant (interaction effect = -.02, SE = .03, p = .602; 95% CI [-.07, .04]). The same is true for the interaction between this variable and authentic leadership in stress at work (interaction effect = -.01, SE = .03, p = .632; 95% CI [-.07, .04]). Both results seem to indicate that perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions did not have a moderating effect, thus rejecting our Hypotheses 5a and 5b. In short, based on these results, we concluded that neither organizational identification (moderated mediation effect = -.01, SE = .01, 95% CI [-.04, .01]) nor perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions (moderated mediation effect = -.00, SE = .01, 95% CI [-.03, .02]) exerted a consistent moderated mediation effect on the relationship between authentic leadership and organizational dehumanization/stress at work. Figure 1 Simple Mediation Analysis of Organizational Dehumanization in the Relationship between Athentic Leadership and Stress at Work for Study 1 (coefficients are reported inside the figure) and Study 2 (coefficients are reported outside the figure). Direct effect including the mediator are in brackets. Coefficients are standardized.   *p < .05, **p < .01. Figure 2 Moderated Mediation of Organizational Identification (moderator 1) and Perceived Frequency of Leader-Follower Interactions (moderator 2) in the Relationship between an Authentic Leadership Style and Sress at Work that is Mediated by Organizational Dehumanization, for Study 1. Coefficients are standardized.   *p < .05, **p < .01. We performed a study to analyze the predictive ability of authentic leadership on organizational dehumanization and stress at work. The results, as expected, highlighted that perceiving an authentic leadership style within their supervisors predicted a lower tendency among workers to consider that their companies regarded them as tools for achieving companies’ goals. Moreover, perceiving this leadership style among their supervisors was also related to an adequate balance between efforts made by workers during their daily routines and rewards they received for their performance (i.e., lower levels of stress at work). In addition, the results indicated that perceived organizational dehumanization partially mediated the relationship between perceived authentic leadership and stress at work. Meanwhile, organizational identification or perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions did not have a clear role in moderating previously identified relationships among variables. Based on these results, it seems that authentic leadership protects workers against stress at work by making them feel that they are valued as humans (avoiding perceived treatments as machine-like) within their companies. Thus, based on present evidence, we can conclude that this leadership style has a positive influence on workers by protecting them against pervasive consequences of organizational dehumanization. However, even when this study highlights possible practical implications, such as the need to promote this positive leadership style to confront destructive (Einarsen et al., 2007) or abusive (Caesens et al., 2018) styles, the exploratory nature of this study could be a limitation in terms of support for the effect we identified. Therefore, to provide more empirical evidence that allows us to confirm the protective role of an authentic leadership style, we conducted a preregistered direct replication of our own study (e.g., Lindsay, 2017) to test and confirm the same hypothesis from this study with a second sample of workers. Study 2 In this study, we aimed to confirm the protective role of an authentic leadership style in organizational dehumanization and stress at work, which we identified in the previous study, by providing a direct replication of our previous study. Thus, we carried out this confirmatory study by using the same procedure as in the previous study to confirm that an authentic leadership style negatively predicts workers’ perceptions of organizational dehumanization (Hypothesis 1) and stress at work (Hypothesis 2). Additionally, we aimed to confirm that perceived organizational dehumanization mediates the relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we aimed to replicate the absence of a consistent moderating effect of both identification with the organization (moderator 1, Hypotheses 4a and 4b) and perceived frequency of leader–follower interactions (moderator 2, Hypotheses 5a and 5b) in the aforementioned relationships. The preregistration of the procedure and hypotheses of this confirmatory study can be found online (osf.io/jy8ve). Participants. We applied the same sample size calculation as in the previous study (minimum participants = 652; one predictor, f2 = .02, α = .05, 95% power). The final sample was composed of 913 workers (482 women, 431 men, Mage = 39.16, SD = 10.05) drawn from the general population (see Table 1 for full details). The procedure was identical to that of the previous study. Measures. Once the participants had agreed to participate, they were presented with the same measures as in the previous study: authentic leadership style (α = .95) (relational transparency, α = .85; internalized moral perspective, α = .80; balanced processing, α = .83; and self-awareness, α = .87), organizational dehumanization (α = .92), stress at work (extrinsic effort, α = .79; reward factors, α = .77), organizational identification (α = .86), and perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions (α = .75). Finally, participants answered the demographic information and questions related to the characteristics of their institutions as in the previous study. Procedure. We followed the same data collection procedure as in Study 1. First, as in previous study, we computed descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the measures included in the study (Table 2). The results replicated previous findings, as authentic leadership was negatively related to organizational dehumanization and stress at work, whereas it was positively related to organizational identification and to the perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions. Second, results from regression analyses identified the expected pattern of results: authentic leadership negatively predicted organizational dehumanization and stress at work, even when including moderator variables in the model (Hypotheses 1 and 2, Table 3). Finally, we computed mediation analyses to test the indirect effect of organizational dehumanization in the relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work as in the previous study (PROCESS; model 4, bootstrapping 10,000 samples, 95% CI; Figure 1). The results indicated that organizational dehumanization partially mediated the relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work (indirect effect = -.14, SE = .01, 95% CI [-.18, -.10]), thus confirming Hypothesis 3. Moreover, we also computed moderated mediation analyses by using organizational identification (moderator 1) and perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions (moderator 2) in the relationship between an authentic leadership style and stress at work (mediated by organizational dehumanization) as in the previous study (PROCESS, model 10, bootstrapping 10,000 samples, 95% CI; Figure 3). The results indicated the interaction between authentic leadership and organizational identification in organizational dehumanization was significant (interaction effect = -.05, SE = .03, p = .044; 95% CI [-.11, -.01]), and the interaction between authentic leadership and organizational identification in stress at work was not significant (interaction effect = .01, SE = .02, p = .616; 95% CI [-.04, .06]), supporting Hypotheses 4a but not 4b. Moreover, results indicated that there was no significant effect of the interaction of authentic leadership and perceived frequency on leader-follower interactions when predicting both organizational dehumanization (interaction effect = .01, SE = .03, p = .891; 95% CI [-.06, .06]) and stress at work (interaction effect = -.03, SE = .03, p = .390; 95% CI [-.09, .03]). Thus, Hypotheses 5a and 5b were rejected. In short, in this study, we did not identify a moderated mediation of organizational identification (moderated mediation effect = -.02, SE = .01; 95% CI [-.04, -.01]), nor of perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions (moderated mediation effect = -.00, SE = .01; 95% CI [-.01, .02]). Figure 3 Moderated Mediation of Organizational Identification (moderator 1) and Perceived Frequency of Leader-Follower Interactions (moderator 2) in the Relationship between an Authentic Leadership Style and Stress at Work that is Mediated by Organizational Dehumanization, for Study 2 (confirmatory). Coefficients are standardized.   *p < .05, **p < .01. In this study, we carried out a confirmatory study with similar results to the ones we identified before: authentic leadership protects workers against organizational dehumanization and promotes the balance between efforts and rewards workers received when performing their daily routines (i.e., less stress at work). In addition, as expected, organizational dehumanization partially mediated the relationship between authentic leadership and stress at work. Meanwhile, this mediation analysis seems to not be moderated by workers identification or contact with leaders. Thus, authentic leadership might have a particularly positive effect on workers who identify with their companies. General Discussion The purpose of this research was to explore the relationship between an authentic leadership style and organizational dehumanization perceptions. Particularly, we aimed to explore whether (a) authentic leadership is a protective factor against organizational dehumanization perceptions and stress at work, (b) organizational dehumanization mediates the relationship between an authentic leadership style and stress at work, and (c) there is a moderating role of workers’ identification with the company and perceived frequency of leader-follower interactions in the relationships between an authentic leadership style, organizational dehumanization, and stress at work. Our results are consistent with previous literature on social exchange relationships in the workplace, which indicates that treatment received from the supervisor impacts overall perceptions of the organization (e.g., Molero et al., 2019; Shoss et al., 2013). Moreover, these findings expand the growing literature on organizational dehumanization and confirm the relevant role of supervision styles in organizational dehumanization, which has been previously addressed (Caesens et al., 2018; Christoff, 2014). Specifically, our research contributes to the identification of protective factors that reduce organizational dehumanization. This pattern of findings is complementary to previous research on an abusive leadership style, which promotes perceptions of being valued uniquely as a tool for the company and has detrimental consequences for workers’ well-being (Caesens et al., 2018). Our data indicated that an authentic leadership style fuels perceptions of being regarded and recognized as a human being within the company, thus promoting positive outcomes among workers (i.e., less stress at work). In general, both leadership styles (i.e., abusive and authentic) addressed in relation to perceived organizational dehumanization have opposite and complementary consequences for workers. Thus, it might be possible that both leadership styles represent different extremes of the same construct: negative behaviors or attitudes of an abusive leader (Tepper, 2000) could be the opposite of positive behaviors or attitudes that authentic leadership displays within a company (Walumbwa et al., 2008). To provide evidence of the possible complementary role of both abusive and authentic leadership styles, further research is required. Implications of these findings should also be taken into account. Previous research addressed the need to eliminate or lower abusive or destructive attitudes and behaviors among supervisors to reduce perceived organizational dehumanization (Caesens et al., 2017, 2018). However, the absence of these detrimental factors (i.e., abusive behaviors or attitudes) does not imply that the working environment will potentially fulfill workers’ needs or promote their well-being. Only by actively promoting attitudes and behaviors that correspond with an authentic leadership style will workers fulfill their needs (Azanza et al., 2013; 2015). In this sense, organizations should be interested in increasing awareness among their managers regarding the importance of their roles, and the promotion of a quality of life and positive attitudes toward everyone’s job. As organizational agents, they are responsible for perceptions and attitudes toward the entire organization. Despite the fundamental role played by leadership in workers’ well-being and performance in the organization, we acknowledge that in the present data, organizational dehumanization has only a partial effect on the relationship between perceived authentic leadership and stress at work. Moreover, we are aware that the protective role of an authentic leadership style could be potentially undermined when workers perceive that they lack other key factors within working environments. We take into account that workers’ well-being and performance are triggered by several factors, such as status of their positions (Valtorta et al., 2019a), their working conditions, types of tasks they are assigned (Andrighetto et al., 2017; Taskin et al., 2019), or relationships with their co-workers (Reicher et al., 2005). Further research is needed to establish the extent to which authentic leadership can protect workers, even when other detrimental conditions are present, such as dehumanized environments or workers performing objectifying (i.e., repetitive, fragmented) tasks. By comparing the role of these variables as predictors of similar outcomes, or by analyzing the extent to which these processes could act as underlying mechanisms in the relationships studied, we should be able to provide a more complex view of the protective role of an authentic leadership style. Interestingly, covariates did not have a major effect on the relationships tested. On the one hand, workers’ identification with their companies did not moderate the relationship between authentic leadership and organizational dehumanization at work. Future research could clarify whether both positive and negative supervision styles have a more intense effect on organizational dehumanization in workers with high levels of identification with their companies. On the other hand, contact with leaders did not show a moderation effect on mediation analysis. This result could show that in order to exert a positive leadership style it is not necessary to establish higher levels of contact with workers. Contact would not be a relevant condition to increase the relationship between an authentic leadership style and organizational dehumanization. However, the role of contact in the relationship between an abusive leadership style and organizational dehumanization could be more relevant. Thus, more research is necessary to confirm the absence of the relationship between contact with leaders, leadership style, and organizational dehumanization. Nevertheless, we are aware of the limitations of this research. First, the present work would have benefitted from addressing more psychological consequences apart from stress at work (e.g., turnover intentions, mental health issues, performance; Salgado et al., 2019) so as to reinforce our argument about the protective role of an authentic leadership style against organizational dehumanization. Second, even though the two studies were conducted with a large number of workers from different organizations, and although we consistently identified the same pattern of results, we also acknowledge the correlational nature of our research. Future studies could enrich present results by experimentally manipulating leadership style (i.e., authentic vs. non-authentic) to generate experimental evidence that confirms our results and leads us to explore the causal link between variables. In short, the present research identified the role of authentic leadership in promoting workers’ well-being and in protecting them against detrimental consequences of perceiving that they are treated as less than human within their organizations. This study makes a significant contribution to the body of knowledge of the relation between employees’ well-being, organizational dehumanization, and leadership style. The implications of this research study for management supervision and training in leadership styles are important. Even when detrimental leadership styles or conditions affect workers, these findings highlight the need to refocus our attention not only on factors that hurt workers but also on those that actively promote their recognition as human beings. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Sainz, M., Delgado, N., & Moriano, J. A. (2021). The link between authentic leadership, organizational dehumanization and stress at work. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 85-92.https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a9 References |

Cite this article as: Sainz, M., Delgado, N., and Moriano, J. A. (2021). The Link Between Authentic Leadership, Organizational Dehumanization and Stress at Work. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 85 - 92. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a9

ndelgado@ull.es Correspondence: ndelgado@ull.es (N. Delgado).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef